Using war-dairy entries as a guide my husband and I have followed my grandfather, POW Charles William Palmer, a Private in the 48th Battalion of the A.I.F., through France to Bullecourt, his place of capture on 11 April 1917, then on to the many villages in France where he was forced to work for the Germans. After a long seven months of capture he finally reached Germany where he was placed for short periods in two different POW Camps. In this post we will discover how Charles spent the last 11 months of WW1.

If you wish to start the story from the beginning please go to What is this Blog?

Then …

After spending 10 days in the prisoner-of-war camp at Güstrow in northern Germany, Charles was assigned to work for a local iron foundry near Lübeck. He writes:

28 December 1917

“On the morning of the 28th most of us was [sic] sent off in Batches some to farm’s, others to different factories. I was sent to a place called Lubeck with two Tommies which place we arrived at a [sic] midday and was then taken on to the Hockovenwerk’s Iron Foundry…”.

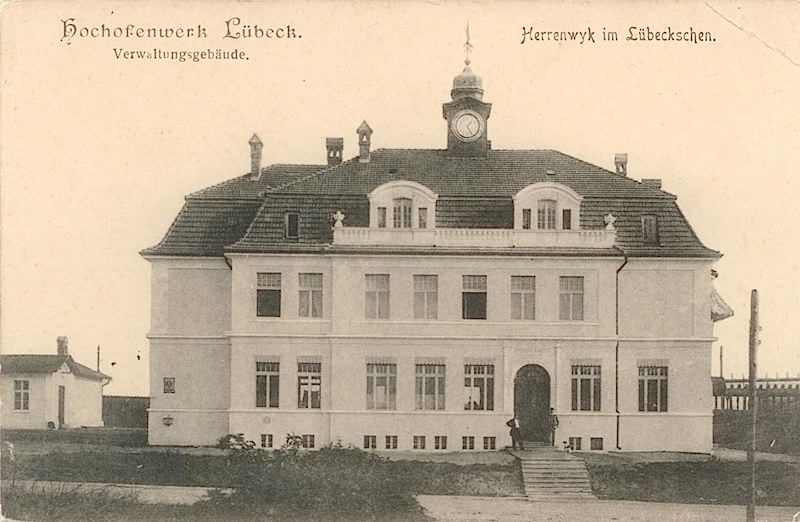

Lübeck is a beautiful town positioned 110kms to the west of Güstrow and 70kms north-east of Hamburg. While Charles passed through Lübeck, it is doubtful that he would have actually spent any time in the old town as his final destination, the Hochofenwerk (blast furnace), was some 14kms from the main centre in the urban district of Herrenwyk. Building of the first blast furnace commenced in May 1906 and the plant began production the following year. By 1909 there were three blast furnaces in production at the site.

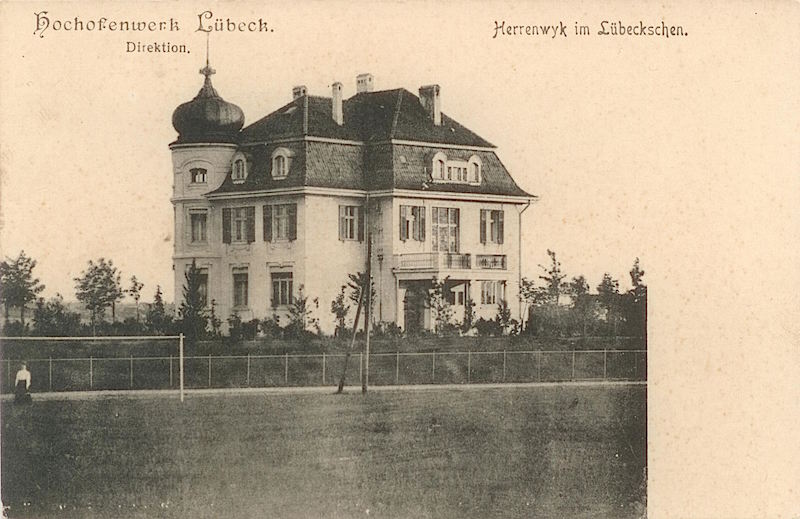

Alongside the plant, a factory settlement (Kolonie Kücknitz) was built to house the workers, together with a store selling food and household goods. A slaughterhouse was built to provide meat and there was a bakery on site. Schooling was also available, but only for the children of those who ‘managed’ the sprawling industrial site; not for the workers. An impressive house was built for the General Manager of the business.

Pig iron was in huge demand to support Germany’s war effort. Forced labourers, these being civilian migrant workers who were classified as “hostile aliens” once war broke out, formed the bulk of the foundry’s workforce during the war. The workforce was augmented by prisoners-of-war.

Charles sheds some light on the living conditions at the foundry when he writes:

“Started work the next morning Saturday [29 December 1917] no time lost in getting one out to work, some of us have very good quarters here others have a vile place being packed in a building like sardines one could expect nothing better from this Company as it is considered by all German’s [sic] as the worst factory in the whole of Germany mostly civil Belgians are working here under compulsion although [sic] they have no sentry with them when at work, they are nearly as bad off as we are, for they cannot leave the village.”

The prisoners’ shifts at the foundry were exhausting:

“I with the other prisoners where [sic] subject to very harsh treatment our hours of Labour where [sic] 12 hrs per day and 24 hrs every other Sunday, one week night and the other day shift…”

“…the only time one got a spell here was when the Oven’s [sic] used to Burst it was not for long though, for they repaired them in 3 or 4 hours.”

Apart from the atrociously long hours the work itself was punishing:

“… all the British prisoners where [sic] kept at the hardest work in the factory, that was shovelling & trucking the different materials for the making of pig iron or steel most of the loads we had to bring in was [sic] about 900 kilos per truck average two trucks per charge per man & upwards of 14 charges per shift by the time our shift was finished we where [sic] dead beat, the Sentries over us where [sic] paid extra money by the firm to keep the prisoners on the go from start to finish.”

As well as the long hours and the gruelling nature of the work, the prisoners also had to contend with the cruel treatment often metered out by the guards.

“Two Russians where [sic] killed here by the Sentries, Several Frenchmen where [sic] layed out for awhile also one of our fellows.“

Food was limited:

“Ration’s [sic] was one slice of bread and a pint & half of soup per day.”

“… if it had not been for the Red Cross parcels I do not think many of us would have left there alive. When they came we gave our soup rations to the Russians who where [sic] very thankfull [sic] for it.“

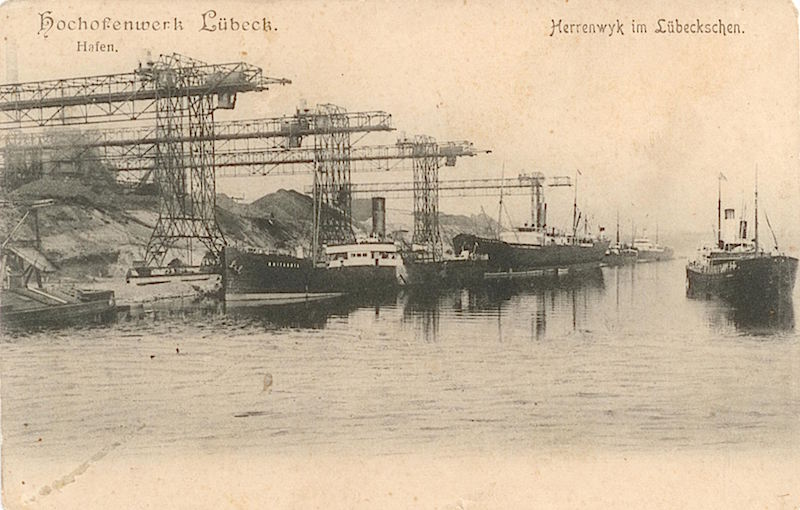

“A good many of these [the Red Cross parcels] where [sic] pilfered still we did not do to [sic] bad for they came fairly regular, we sometimes got a parcel of English paper’s which where [sic] smuggled in the works by some of the English sailor’s who where [sic] mostly at work unloading ships from Norway & Sweden when no ships where [sic] in a few of them where [sic] sent to the oven works, they got a good deal of English papers which caused the Germans a good deal of trouble. We received from 90 phennig’s to 1 mark 50 phennigs per day whilst at these works.”

The following photograph of a group of POWs was, I believe, taken at the Hochofenwerk. Charles is at the right hand end. This photo and some portraits of his fellow prisoners were all produced as postcards with the marking Atelier Schnoor, Lübeck, Sandstr. 17, II. on the reverse side. The Phone Book from that time confirms the photographer as Bernhard Schnoor. He had a studio in Lübeck and was probably brought out to the Hochofenwerk to take these formal group and portrait photos. The portraits I have referred to can be found on the Postcards & Photos page of this site.

Charles endured 11 long months working at the Hochofenwerk near Lübeck. As the prisoners sometimes had access to smuggled English newspapers we can assume that news of peace was not unexpected. When they heard that the Armistice had been signed on 11 November 1918 the relief for Charles and the other prisoners must have been intense. Charles must have often wondered how long he could keep up the pace of his existence in such a hostile environment – long enough to make it home?

On 18 November 1918 Charles writes:

“… having heard that the Armistice was signed all the prisoner’s working here struck work, there must have been about 300 prisoners of war here. Mostly Russian & French only 59 British the Manager offered us all 10 mark’s per day if we would work till repatriated. No not 50 he was told, we where [sic] then shut up in our barracks till the 21st when we entrained for Gustrow, there to wait repatriation.”

One can only imagine the spirit with which they told their captors, No!! We will not continue to work even for 50 marks per day!!

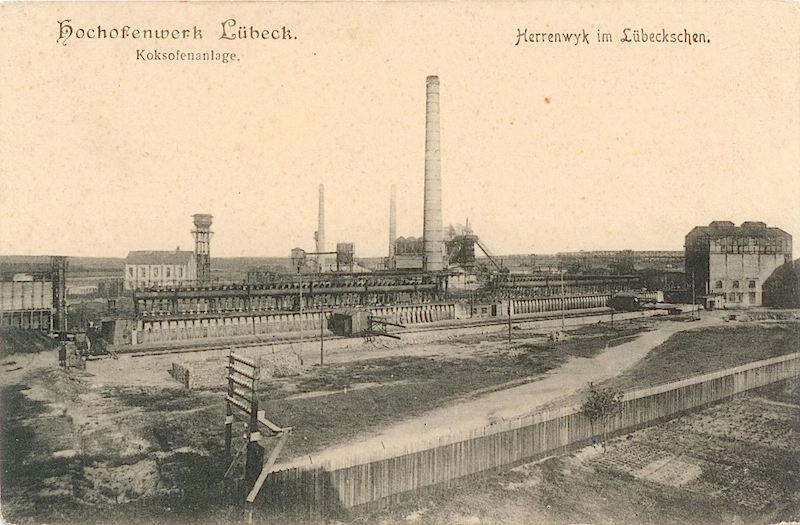

During his time at the Hochofenwerk Charles collected a number of postcards that are shown below.

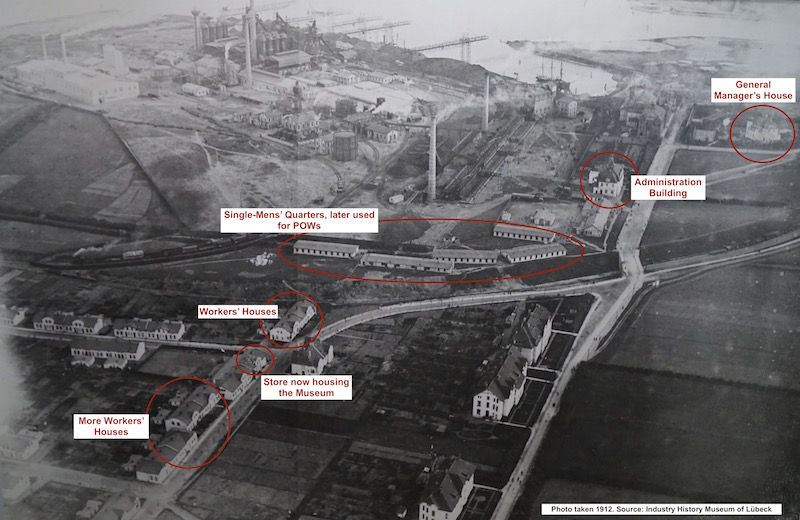

I have annotated the following 1912 aerial photograph of the site to show the location of some of the buildings pictured in the postcards. You can also see the harbour at the top of the photo.

The impressive General Manager’s house shown below is still in existence. A present-day photo of the house is included later in this post.

And now we will explore what remains of the Iron Foundry site in 2016.

And now …

Planning for this part of our trip started many months prior to our departure with research into the town of Lübeck and efforts to trace the Hochofenwerk referred to in Charles’s diary. I was able to locate the website for the Industrial Museum History Workshop Herrenwyk. This Museum was established in the early 1980s and is located in the former shop on the site of the workers’ settlement next to the actual blast furnace.

I emailed the Museum and was delighted to receive a response from historian, Christian Rathmer who offered his assistance during our visit.

We timed our arrival in Lübeck to coincide with the Sunday opening hours of the Museum, and spent the afternoon browsing the exhibits. Although all the captions and information boards are written in German the presence of many large photographs and displays of artifacts and tools gave us a real sense of the scale of the factory and the tough working conditions on the site; not only during the war years, but also prior to and after that period.

The following day we returned to the Museum to meet with historian, Christian Rathmer and Dr Wolfgang Muth, former director of the Museum. I am so very grateful to them both for giving up their time to talk with us about the history of the factory. They were able to expand on the information we had gleaned from our visit the day before, although it seems that information about the prisoner-of-war workforce at the factory in WW1 is scant. Though brief, I was able to share the few facts that Charles had documented in his diary.

We then set out on a walk around part of the original 81 hectare foundry site. We were surprised to learn that a number of the original settlement buildings are still in place, although they are not all from the First World War era. All along I had been keen to discover where Charles may have been housed during his time at the foundry. We were shown a run of buildings used prior to the war for housing single men. Wolfgang believes that these were used during WW1 to house the POWs, so it is highly likely that Charles was housed here and, in his words, “packed in … like sardines”. These buildings are now private residences.

Our visit to Herrenwyk, both the Museum and the foundry site, was a very special part of our journey to walk in Charles’s footsteps during his time as a POW.

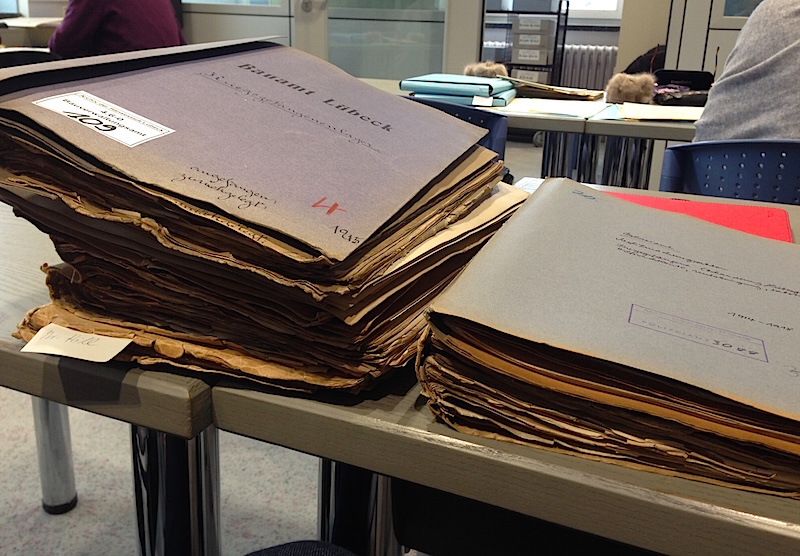

Prior to our visit Christian had passed on the details of my search to Jan Lokers, Director of the Hansestadt Lübeck (Archive of Lübeck). In a timely coincidence a new book was launched the week we were in Lübeck containing a chapter written by Jan entitled: “Prisoners of war and “hostile aliens”: captivity and forced labor in Lübeck during the First World War”. The book is in German, but I am working on translating Jan’s chapter and feel sure that it will reveal more interesting and relevant facts to help expand our understanding of this time.

I had made contact with Jan Lokers before our visit and he kind sent me a list of files relating to the use of prisoner-of-war labour in and around Lübeck in WW1. I pre-ordered around 23 of these files for use in the Archive reading room during our stay in Lübeck and spent a fascinating day going through them all. My lack of understanding of German was, of course, a great disadvantage! Even so, I was able to dip into interesting 1915 correspondence between the Hochofenwerk management and “Berlin” repeatedly requesting permission to use POW labour; I ploughed through lists of names of individual workers but concluded that most were likely to have been “forced labour”, rather than POWs; and found correspondence that discussed the conditions under which the POWs were being kept at the Hochofenwerk. So, while I was not able to discern any extra information relating directly to Charles, it was a tantalising glimpse into the records that are held by the Archives.

In talking with both Christian and Wolfgang it is interesting to discover how little research as been done about the POWs in Lübeck in WW1. The new book is a welcome addition to the research, but I gained the impression that it is an area still ripe for further investigation.

Looking back at the work assignments handed to POWs it is clear that they varied in nature. Many were sent to farms as agricultural workers and this could sometimes mean extra food as they tilled the crops, and a warm bed in the farmer’s barn. For Charles, though, there is no doubt that it was a very arduous work assignment he was handed those 11 months previous when he was sent out to Lübeck from the Güstrow POW Camp.

Through every stage of this journey it has become more and more obvious that my grandfather, Charles William Palmer, was a tough and resilient man. He was a survivor. He endured 11 months working as a POW in the iron foundry near Lübeck and, for the first time since his capture, news of a move, this time back to Güstrow on 21 November 1918, must have filled him with hope. Repatriation was on the horizon.

In the next Blog post we will see Charles repatriated back to England, before heading home to Australia.

* In the quotes from Charles’s diary I have used [sic] to indicate when an error in the text is part of the original, rather than typographical.

– All photos taken on 6 and 7 November 2016 by Kaye Hill –

Related links:

Hochofenwerk Lübeck, Wikipedia. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hochofenwerk_Lübeck

Industriemuseum Geschichtswerkstatt Herrenwyk. https://geschichtswerkstatt-herrenwyk.de/de/Home

Lokers, Jan. “Kriegsgefangene und “feindliche Ausländer”. Gefangenschaft und Zwangsarbeit in Lübeck während des Ersten Weltkrieges”, IN “… so blickt der Krieg in allen Enden hindurch”: Die Hansestadt Lübeck im Kriegsalltag 1914-1918, herausgegeben bei Nadine Garling und Diana Schweitzer. Lübeck, Archiv der Hansestadt, 2016. Seite 67-88.

This was very interesting to read because I am from Lübeck. The thing is, they taught us all kind of stuff about our city in school, like facts dating back to the late Middle Age, or we learned a bit about the Hanseatic League too. From grandma and grandpa I learned how things were at the end of the WW2 and how it was afterwards. Museums that I visited with the school class back then, showed us picture of the WW2 time and so on. I don’t know a lot about the WW1 period of our city, I didn’t even know we had POW’s here. Thanks for sharing your information’s with us and the historians.

LikeLike

Hi Dennis – thanks for taking the time to leave a comment on my blog. I loved visiting Lübeck – what a delightful city! When I started researching my grandfather’s time at the Hochofenwerk during WW1 I did not anticipate that there would be so little known about that period in Lübeck’s history. It is really interesting to hear your comment that the WW1 period was virtually overlooked in your schooling. There is still so much more to uncover! Best wishes, Kaye

LikeLike